I sometimes take my very life in my hands when I suggest that a certain tree happens to be spoiling a pretty good golf hole."

—A.W. Tillinghast, 1937

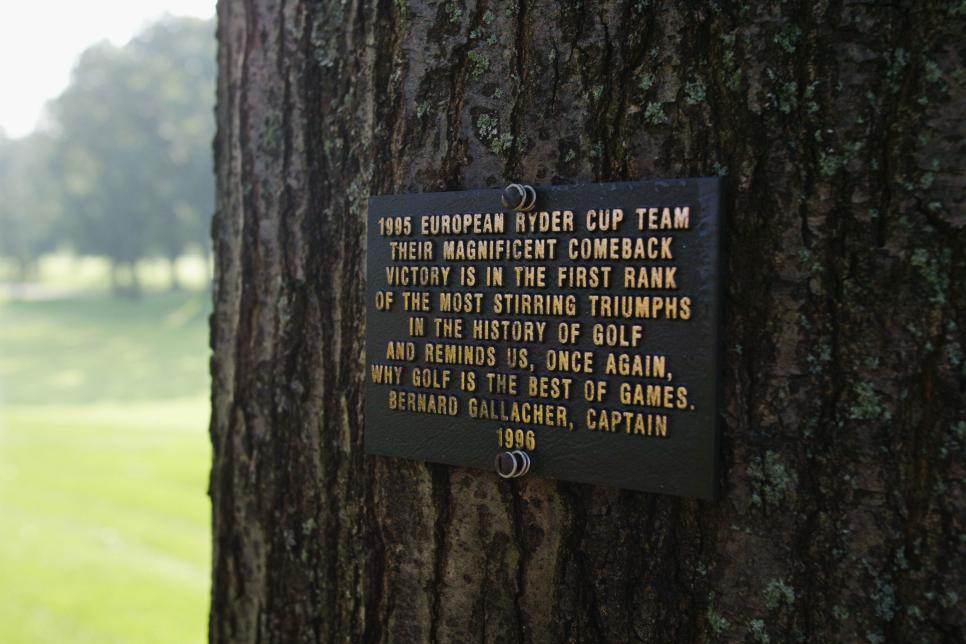

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — Let's start here: The word "oak" is in the name of the club, and the great reasonable fear is that when you remove trees, you remove some of the spirit of a place like Oak Hill. When you consider the fact that the oak trees in particular occupy such a romantic place in the club's history that a few on the "Hill of Fame" by the 13th hole of the East Course, site of this week’s PGA Championship, bear plaques commemorating everyone from Jack Nicklaus to Nancy Lopez to Dwight Eisenhower to the European Ryder Cup team that won here in 1995, you simply can't wield the proverbial axe without a little controversy.

Just ask another course with "oak" in its name, Oakmont Country Club. As Peter McCleery wrote for Golf Digest in 2002, the famed Pennsylvania course led the increasing national trend of serious tree removal, cutting down an incredible 3,500 trees in a restoration product, and 15,000 over 25 years. "There were factions, a threatened petition, prayers for the trees’ survival from a neighboring church, even a whiff of a lawsuit," McCleery wrote. In the end, though, the restoration went through and the reception was overwhelmingly positive.

That's a common theme at places like Merion, Winged Foot, and many other mostly eastern courses where tree growth has a way of sneaking up on superintendents. There are some classic problems with too much tree coverage, including the way it can change strategy and course management for players over time, often in ways that conflict with the intent of the original design. The most pressing issue, though, is far simpler: Trees fight grass. They inhibit air circulation, and they block sunlight. This is most acutely felt on greens and tees, where, as McCleery put it, "under too much shade will be subject to a general thinning of the turf, or in extreme cases, no turf at all." That paves the way for wear and tear from golfers, and for weed invasion.

Oak Hill of the past is a classic example of how things can go wrong. When the club tried to convert the greens on the East Course, hosting its seventh men’s major this week, to bentgrass, the prevalence of large, mature trees made the conversion incredibly difficult, and they ended up being describe in an article for Golf Course Industry as a "mix stand of annual biotype Poa annua and bentgrass" that hurt the greens. A former superintendent named Kevin Green showed how "calculated tree removal" could help the bentgrass thrive on the rebuilt greens on 13 and 15, and serious clearing of trees actually started after the 2013 PGA Championship.

In 2016, Andrew Green, at that time a little known architect specializing in restoring old courses, came on board to oversee the new changes, and the official restoration—based in some cases on original drawings by Donald Ross—began in 2019. By that point, the tree removal was well underway. That was far from the only change Green oversaw (he rebuilt bunkers, removed a pond on the 15th hole, built the new fifth and sixth holes from scratch, and more), but the trees were always going to be the biggest sticking point with members. They are a form of life, after all, and people develop attachments to trees that are emotional in nature. And yet, they managed to earn the approval of more than two-thirds of club members.

How did they pull it off? As Green explained on the Golf Channel this week, they held a town hall attended by more than 100 members and made the point that this wasn't going to be like Oakmont—there would be a balance, and Oak Hill would always have its oak trees. They also explained how it would help the grass, and the playability of the course, and how it would respect and highlight the course's history, all the way back to its Donald Ross origins. That didn't mean the members were completely convinced, or that he avoided "tough conversations." But nobody could accuse the Oak Hill team of not giving a thorough explanation of what they were doing and why they were doing it.

That convinced enough members for the project to go through, and it's important to note that they had already made compromises in this direction; even some trees with plaques on the Hill of Fame had been removed long before Green arrived, and the plaques transferred to nearby trees. When Green explained that they would protect trees that held strategic and aesthetic value, but that the turf—the grass you actually play on—had to be the priority. (When asked by The Fried Egg how many trees were removed, Green responded that it was the "right number.")

A view of the Hill of Fame at Oak Hill Country Club.

Gary Kellner

Plates honoring players and non-player on trees surrounding the 13th hole remain, some being moved to new locations when a tree was removed.

Rick Stewart

Rick Stewart

The other truth Green knew is that "little trees become big trees," and once the trees and their canopies grow, overcrowding can occur, and situations emerge where certain trees can even grow into each other in ways that impact their health. He was never afraid to make the "critical decision," even if that meant cutting down more trees with plaques. It was all in the interest of creating balance, which had gone by the wayside through the simple act of growth, along with decades of pursuing major championship golf in ways that pushed the course further and further from its origins.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the restoration has been a massive success, to the point that it's difficult to find any negative criticism even if you're looking very hard. (In at least two interviews, the one piece of critique Green is wary of is the players complaining about the difficulty of the restored bunkers.) There will always be objections to tree removal, particularly on the emotional level, but there's solace in the fact that Green's vision for Oak Hill had its own spiritual and emotional element: rediscovering the soul at the heart of what had become a lost course.