Editor's Note: This article first appeared in Fire Pit Collective, a Golf Digest content partner.

If you’re familiar with the first season of “The White Lotus,” you know the dad—a white, affluent middle-aged father of two. The character’s name is Mark Mossbacher and his testicles are defective. (They’re swollen, per the script.) The dad’s CFO wife is paying the bills at their tony Hawaiian resort hotel, the White Lotus. Maybe there’s a metaphor in all that, I don’t know.

In any event, the ruling era of a certain prominent subspecies—the white, educated affluent middle-aged and older American father—has been unwinding for a while now. Even golf, always behind but now in a state of disruption as never before, is starting to figure that out. The USGA has its first Black president, Mr. Fred Perpall.

Yes, that leaves the PGA Tour, the PGA of America, Augusta National, the CEO of the USGA and every equipment manufacturer that still advertises in Golf Digest and Golf magazine and yada, yada, yada. But there is Fred!

“For years, I was the good guy, you know?” the dad tells his family as the family of four and a keep-the-peace friend dine alfresco at the White Lotus. “I was the one in the room, saying, ‘Hey, that’s not cool,’ to all the chauvinists and bigots. But now I’m the bad guy, or at least, I shouldn’t say anything on account of my inherited traits. I mean, why do I need to prove my anti-racist bona fides?”

“It’s not all about you, Dad,” says the daughter, Olivia. She’s in college and cannot be bothered. With anything. “It’s time to re-center the narrative.”

The phrase is hilariously pretentious and totally apt.

This whole re-center-the-narrative thing comes to mind for me because I was thinking about a sensitive golfing matter: reserving spots for players in PGA Tour events on the basis of their race. Because my feeling about it, as a golfing purist who always has the right instinct on every golfing issue …

I no longer care about my golfing purist feeling about this particular issue because it really is time to re-center the narrative. Look at what’s going on from another perspective.

You can use the w-word all you want. (Woke.) I really don’t care.

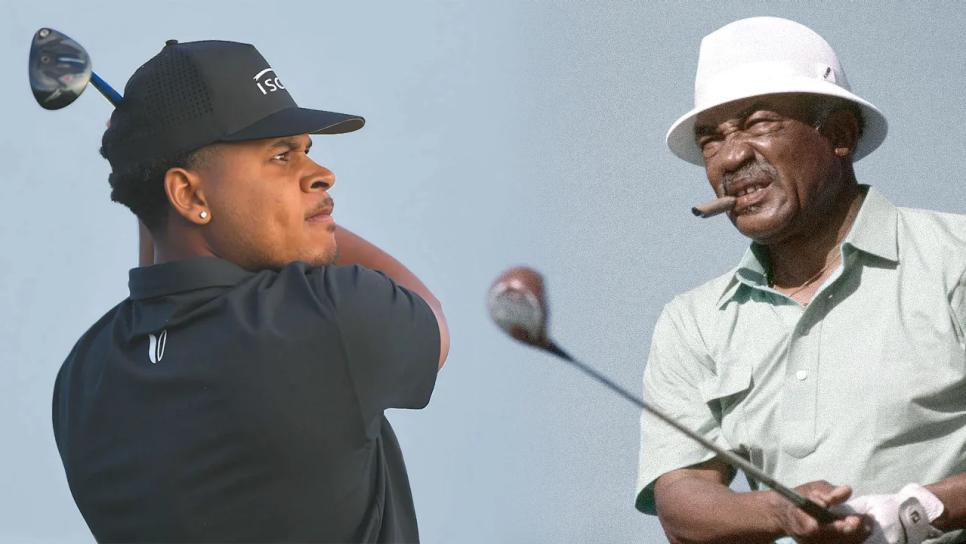

Golf is a great, big, beautiful game. The sport and its culture have enriched every aspect of my life and maybe yours, too. But its racist past—at country clubs, at public courses, on professional tours, at the PGA of America, in the hierarchy of the USGA—is American golf’s original sin. It remains a crime that Charlie Sifford was never invited to play in the Masters, despite winning at Hartford in 1967 and Los Angeles in 1969. It remains a travesty that Pete Brown (below) was not invited to play in the Masters after winning at Torrey Pines in 1970.

I visited and interviewed Brown in the winter of 2014, when he was cogent but failing, in a house on the outskirts of Augusta, Ga., owned by his friend Jim Dent, the former Augusta National caddie who won 12 times on the Champions Tour. It was profoundly moving to talk to this proud, kind man and consider his life and times. He died 14 months later.

So now American golf, at its highest professional level, the PGA Tour, is trying to correct an historic wrong, and it says here …

Do not go there.

Re-center. Re-center. Re-center.

Marcus Byrd will be one of the few Black golfers in the Genesis field at Riviera next week. He got in the tournament as a Charlie Sifford Memorial Exemption, reserved for a player with a minority background. Byrd will play the following week too, at the Honda. He earned that spot by winning a 36-hole event at Torrey Pines that is part of the APGA Tour, sometimes called the Advocates Tour, a series of tournaments founded to give more opportunities to minority golfers.

Are you, in your own way, a golf-mad Mark Mossbacher, proud to call yourself an anti-racist, but ambivalent about whether these paths to a tournament field make sense?

Yep, time to re-center.

Time to listen to Byrd and his remarkable life story. To Kamaiu Johnson (above), who has been chasing the dream for years now. To Aaron Grimes, a promising Black golfer from Compton, in Los Angeles. To Harold Varner III, now signed on to play LIV Golf. (Varner, 32, is not apologizing for anything. He loved his years on the PGA Tour, but the LIV money was irresistible.) To Joseph Bramlett, a 34-year-old biracial golfer on the PGA Tour who has been to medical hell and back in his long golfing life. JB T-7’ed last week at PB. On two occasions, Bramlett played in the L.A. Open, now the Genesis Invitational, as a Charlie Sifford Memorial Exemption, in 2011 (when the spot existed but the name did not) and in 2020.

No, Bramlett’s life and times cannot be compared to Charlie Sifford’s. Bramlett played country-club golf as a kid. He went to an elite private Catholic school outside San Francisco, St. Francis High, Class of 2006. Four years later, not even, he graduated from Stanford. But part of his life story, and for this we are drilling into his family history, makes him an example, and surely an inspiration, for others.

When Bramlett (below) played in the Genesis in 2020, he was asked about Charlie Sifford’s legacy, and this is what he said:

“I think organizations like the Advocates Tour is doing a phenomenal job putting together a full schedule for guys to play and guys to compete with each other. I think there are a million different ways that people can go. I know Cam [Champ] is putting on a junior tournament that’s going to help get young kids of color playing the game together.

“I grew up playing in the Bill Dickey Invitational every year, so I got to meet a lot of great kids through that organization and lifetime friends through it. There are a lot of things that the game can do. I think that this exemption right here is a great platform and I’m really proud to represent that, and as I have more success in my career, I can try to contribute to that as well.”

Represent. Beautiful.

No additional commentary needed, not from this reporter, not when Bramlett speaks about this subject from deep inside it.

Bramlett made his first cut in a major last year, at the U.S. Open. He is a study in perseverance.

Kamaiu Johnson, the same. I spent a fast hour talking to him on the phone the other day. He has an amazing life story. He grew up in central Florida and went to nine schools before the eighth grade, when he dropped out. He lived for some years in his grandmother’s two-bedroom apartment in Tallahassee. There were 10 people in it. Across the street was a city-owned course, called Hilaman. On his 18th birthday, he quit baseball and took up golf. That was a decade ago. He has played a handful of PGA Tour events and he’s now on the Latinoamérica Tour, owned and operated by the PGA Tour. He earned his spot on the tour by being the leading money winner last year on the APGA Tour.

“We deserve these opportunities because, if you’re playing public courses and out of the limelight, you don’t get the opportunities as a junior or an amateur that a Jordan Spieth or a Cole Hammer is going to get,” Johnson told me.

No additional commentary necessary. Mark Mossbacher will tell you that. His daughter will, too. This is not a listening tour. This is listening, period.

Kam also offered this observation. It is not realistic for a player to go from the APGA Tour, 36 holes in a cart, often on short, open courses, to 72-hole events on some of the hardest courses in the world against some of the best players in the world. Tiger Woods used to talk often about the importance of “baby steps.” He used to talk often about beating everybody at one level, then moving up. That was the philosophy he inherited from his father, who came up the ranks of the U.S. Army.

Of course, Richard Williams took a completely different approach with his tennis-playing daughters, Venus and Serena. Growing up in Compton, they played virtually no junior or amateur tennis. When they were revealed to the world, they were ready to beat the world.

Aaron Grimes, a mini-tour player, knows that story intimately. Grimes (below) was interviewed and filmed extensively for a Fire Pit Collective documentary series called “Migrations.” At times he wears a Compton Country Club hat. No, there is no Compton Country Club. He carries a Los Angeles Country Club bag, where he caddies. He took up golf at a par-3 course in Los Angeles called Maggie Hathaway, named for the civil rights leader. In an interview for the documentary, Grimes says, “You get these kids who grow up at these country clubs, they definitely get better access, earlier on. They’re born in the right situation. Guys like myself, I have to work a little harder and be put in that situation.”

No commentary necessary.

Grimes was not a USGA golfer as a kid. He was a Western States Golf Association golfer. That’s sort of a USGA for Black golfers, including juniors. The courses where WSGA events are played are sometimes rough. But it’s golf. As Gus Johnson, a former WSGA president, likes to say, “We want to see indexes going down and GPAs going up.” He cites Grimes as Exhibit A.

There are many others. We just don’t know their names. I should say I don’t.

I didn’t know the name Marcus Byrd until he played his way into the Honda at Torrey Pines last month, during the Farmers tournament. We talked for 40 minutes or so the other day. When he plays at Riviera next week, and at PGA National the week after that, I will be rooting like mad for him to make the cut. That would be a huge achievement, though maybe not a realistic one. He shot 71 and 75 on the two Torrey courses, by which he won the APGA Farmers Insurance Invitational and his spot at the Honda.

Byrd is 25. Can he still make it to the PGA Tour? Well, when Joseph Bramlett was 25, dealing with injuries and overhauling his swing, there was no way to guess that at age 34 he’d manage a top 10 at the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am. But he did.

I’m not pretending that I know Marcus Byrd, at all. But after listening to him talk about his parents and his path in golf and what it means to him and what the Black experience in golf has been like, he is captivating and seems like a great person. He grew up in Washington, D.C., and played a lot of golf at Langston Golf Course. His father agreed to run a driving range that was going out of business in Temple Hills, Md., called Golfzilla, primarily so Marcus could have a place to hit balls. He hit a million of them. His father has since died. Golfzilla has closed. The memory and lessons of both live on in Marcus. His mother’s health is not good. Marcus hopes she can make it to Palm Beach Gardens for the Honda. He caddies at Burning Tree Club, an elite, all-male golf club in Bethesda, Md. Byrd (above) has seen more golf in his 25 years than most people will see in 75.

“You’d like to say golf is color-blind, but it’s not,” Byrd told me. “Once you get in the field, it is. But you got to get in the field."

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Bamberger@firepitcollective.com