Out On His Own

Why a 14-year-old boy is outlawed from playing on his golf team

Luc Esquivel hits in silence, too engaged with carving trajectories through the Knoxville sky to chat. When he does speak, the words “My bad,” or “Agh, sorry” tumble out, prompted by a shot that didn’t follow his directions. That’s the type of 14-year-old Luc is, apologizing for things that don’t need an apology. He’s dressed in a black hoodie, ripped jeans and gray Chuck Taylors, and by himself. If it were up to him, he would be practicing with the high school team. But Luc was not allowed to try out because the Tennessee state legislature said he could not.

It’s hard, Luc says, to have a group of people he has never met take control of his life, to define who he is and just as importantly who he is not. “I have to tell myself to stop thinking about it for too long because I can’t make sense of this,” Luc says. So he hits in solitude, the weight of a lawsuit on one shoulder and the hopes of a community on the other, wanting to stay sharp for a day he knows might not come. This is what he’s good at and what he enjoys, and for now it’s what he has got.

THEY DIDN’T THINK LUC WAS GOING TO LIVE—OR IF HE DID what life he would lead. Shelley Esquivel went into labor at just 31 weeks with twins. One child, Cora, was healthy, but a congenital heart defect was discovered in Luc. He was airlifted to a national children’s hospital in Washington, D.C., for emergency surgery. The procedure didn’t go well, and he went into cardiac arrest and suffered bleeding in the brain. Miraculously, Luc eventually stabilized, but Shelley and her husband, Mario, were warned about possible complications. There was a good chance Luc would never walk. There was a good chance Luc would not be able to talk. There was a chance that Luc would never be “normal.”

Fourteen years later, Luc is thriving. It hasn’t been easy; he has a learning disability caused by the hemorrhage, and he battles dyslexia. He has had multiple operations to fix his eyesight and wears glasses. Still, one would likely never know his trials, past or present. At home in suburban Knoxville, Luc, like most teenagers, appears slightly annoyed that he has been called away from his computer to chat with an adult. He’s big into gaming and digs spicy food. He rolls his eyes when I ask what his favorite TV show is, politely explaining that most people his age watch YouTube channels instead. He says that he has taken an interest in finance. “I notice a lot of teenagers aren’t good with money, like my sister. I tell her all the time she’s going to be broke because she spends so much,” Luc says. “That’s not going to be me.”

Luc is also, or perhaps foremost, a golfer. Growing up he tried several sports, yet none of them held his attention. Golf was different. “I noticed when I played other games, I was always waiting for them to be over,” Luc says. “With golf I’m upset when I know it’s about to end.” He has been playing since he was 10. He was introduced to the game through a friend and immediately signed up for classes at The First Tee. Luc took advantage of an initiative started by PGA Tour pro and Knoxville native Scott Stallings that allowed junior golfers to play for free at local courses. He signed up and played for his middle school golf team. He’s down to a 12-handicap and recently almost broke par at a nearby track, impressive for someone his age who has played for only a few years. Between playing—Luc often goes out with his father, who works in cybersecurity for the military—and range sessions, Luc estimates he practices four or five times a week. “I really got it into gear about a year ago,” he says.

‘IT’S HARD TO DESCRIBE. I KNEW WHAT PEOPLE WERE CALLING ME WASN’T SOMETHING THAT FIT ME.’

It was also about that time, in the winter of 2021, that Luc decided to make something public he had known privately for the longest time. Identified as female and named “Lucy” at birth, Luc sensed differently in his head and in his heart. “Growing up, I saw the things my sister was into and did as a girl, and I was always like, OK, that doesn’t feel right,” Luc says. “It is hard to describe. I knew what people were calling me wasn’t something that fit me.” From an early age he expressed an aversion to dresses and skirts, preferring neutral or boy clothes, and by age 10 Luc told his parents he wished he was a male. In middle school he cut his hair short and loved the way it made him look and feel. He initially asked his family to call him “Luce” (pronounced loose), but unbeknownst to his parents his friends were already calling him “Luc” (pronounced Luke). He expressed fear of puberty, not wanting to develop feminine features. “Then I learned about being transgender,” Luc says, “and I was like, This is how I feel! This is me!”

In describing the past year, Luc wishes there was something more dramatic to pass along about the public transition to being a boy. There is not. “I’m still me. I’m more me than I’ve ever been,” Luc says. He began taking puberty blockers, and his endocrinologist plans to start testosterone treatment when Luc nears 16. Luc admits he still is learning all the vocabulary associated with the community but says he has never felt more comfortable being himself, a conviction aided by the reception of those around him.

“Lucy was always ‘different,’ but I personally did not know why,” says Joei Morton, a friend of the family. “Honestly, it did not matter since love is unconditional, and I love that kid as my own. Then one day he came out as Luc, and everything made sense. His awkwardness as a girl was because he is a boy. Literally, everything about him made sense, and all the puzzle pieces that made up Luc finally fit into place.” Moreover, though teenagers are not known as the most hospitable of creatures to change, Luc’s classmates have accepted and welcomed him. “I was not really surprised when he told me that he wanted to transition,” says Lily Burdine, Luc’s best friend and middle school golf teammate. “I let him know that I support him.”

“You never know how different people are going to react,” Shelley says. “Luc has always been fine doing his own thing. I worry about bullying and harassment, but everyone has been great. His fellow students have been great. His teachers have approached me saying, ‘You know, you have a safe space in our classroom, and we’re proud of Luc. All the support was surprising, in the best way.”

Now recognized as a male by his peers, Luc had his eyes on the Farragut High School golf team. (In Tennessee golf is a fall sport, but tryouts are in the spring.) It wouldn’t be easy; he would be moving back a set of tees, and his fellow boys were more physically developed. “I felt good about my game,” Luc says. “I was looking forward to measuring how it compared with everybody else.”

Luc never got the chance.

IN MARCH 2021, TENNESSEE GOV. BILL LEE SIGNED SENATE Bill 228, which requires transgender athletes in middle and high school to compete under their assigned sex at birth instead of the gender they align with. The bill is among a wave of similar legislation nationwide; this year more than 30 states are considering various iterations of youth sports bans for transgender kids. The legislation is without majority support: According to a PBS poll in 2021, only 28 percent of Americans favor bans on transgender student athletes.

The general contention of those promoting these bills is that they are necessary to maintain the integrity of women’s sports and the safety of those competing. Lee echoed similar beliefs when signing the bill, stating it would “preserve women’s athletics and ensure fair competition.” Those in opposition say the bills are an attempt to single out the transgender community. Senate Bill 228 is one of many transgender-targeted policies helmed by Lee—including healthcare regulation, bathroom access and restricting sex education—that critics view as discriminatory. “The justification for the sports bans are absurd,” says Sasha Buchert, senior attorney for Lambda Legal, the oldest and largest organization in the country for advancing and protecting the civil rights of LGBTQ people. “It’s all based on speculation and hypotheticals.” Tennessee state senator Joey Hensley, who sponsored Senate Bill 228, said during the bill’s ratification that he was unaware of any issues involving transgender athletes in Tennessee, instead saying it could be a problem “over time.” Evidence suggests these bills seek to resolve a problem that does not exist. In Utah, where the state legislature is also weighing a transgender sports ban, a LGBTQ advocacy group says there are just four registered transgender children out of 75,000 student-athletes at the high school level. Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, in vetoing the bill, remarked, “Rarely has so much fear and anger been directed at so few.”

In the case of University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas, who in March 2022 won the 500-yard freestyle at the NCAA women’s swimming and diving championships, becoming the first known transgender athlete to win an NCAA Division I championship in any sport, the win was celebrated and protested. Thomas’ case is rare, but it is the scenario that gives mandates like Lee’s justification for their existence. It’s also a precedent not completely copacetic with those targeted by the bans; Thomas, for example, has undergone multiple years of hormone-replacement therapy as part of her transition and competes at the highest amateur level. Most of the legislation in question addresses children who have yet to or are just beginning puberty and are participating on high school and elementary teams.

Many of these state bills mirror each other—literally. Dozens of states have the same word-for-word language in their transgender legislation. This is most likely a byproduct, according to Buchert, of a group opposing LGBTQ liberties supplying a template for lawmakers to build from. But Senate Bill 228 is relatively unique among the transgender bans because it is total in its restrictions. Most transgender legislation restricts only trans girls from playing high school sports, but Senate Bill 228 bans all middle school and high school trans athletes from competing in accordance with their gender identity, boy or girl, no matter the sport.

Luc’s transition coincided with the passing of Senate Bill 228. It wasn’t a surprise. Luc and the family followed the news and could see where the legislation was headed. Initially he didn’t let the bill faze him. Shelley and Mario say Luc has always been a mellow kid, a temperament they attribute to the adversity he had to overcome early in his life. If anything Luc thought it was ironic; just four months before the state had celebrated Vanderbilt’s Sarah Fuller, who became the first female to play in a Division I football game when the goalkeeper-turned-placekicker kicked off against Missouri.

So, Luc asks, shaking his head, he could identify as a female and play college football but he, a transgender boy, is not allowed to play high school golf?

“At the time I felt like—is this going to sound mean?—the Tennessee lawmakers were being drama queens,” Luc says. “They acted like they were cleaning up a problem, but they were really just creating a new mess. I was just like, Whatever.”

Six months after the bill’s passage, a different reality and disposition set in. All Luc wants to do is play golf, to be a part of a team. The happy-go-lucky kid was devastated that right was stripped, made worse by watching his friends go out and join the team. These sentiments are rampant within the transgender community: the 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health found that 62 percent of trans youth suffered from depression and 42 percent seriously contemplated suicide.

“I have always understood his love for golf, and it is so disappointing to see him being denied the opportunity to play with the other guys,” Burdine says. “His dedication and attitude would make him an asset to the team.”

When Senate Bill 228 passed, the American Civil Liberties Union, a nonprofit organization that defends and preserves individual rights and liberties, spread the word that it would help anyone affected by the law. When Luc began feeling the hurt from being prohibited from trying out, the family explored what could be done to fight back. Luc and his family also understood the gravity of doing so. Any legal route would likely place Luc in a very public-facing position. Luc is not one for spectacle and despises attention. He’s a shy kid by nature. He’s also 14, and most 14-year-olds would like to stay in their rooms and be left to themselves.

But the more Luc thought about the bill, the more he realized his pain was shared. “I don’t normally get angry, but this makes me angry,” Luc says. “I just want to play golf. Then I was like, OK, how about other people? Not just in golf, but other sports and how they would feel if they didn’t get to play on their teams. That’s when I said I really want to do this—for myself but also for everybody else.”

ON NOV. 4, 2021, THE ESQUIVEL FAMILY, THE ACLU AND Lambda Legal filed a lawsuit against Gov. Lee and the Board of Tennessee Education, asserting Senate Bill 228 is in violation of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution and Title IX of the Education Amendments.

“SB 228’s sweeping exclusion of all transgender students from participation on any athletic teams consistent with their gender identity, regardless of the circumstances, is disconnected from its own stated purposes of protecting the athletic opportunities and safety of cisgender girls,” the lawsuit reads. “Excluding [Luc] from the boys’ golf team does nothing to further those purposes.”

“The bill is supposed to be about sports, but this is not about sports,” says Buchert, who is aiding the Esquivel family’s legal battle. “In my opinion, this is to segregate and discriminate against trans people and carve them out of life.”

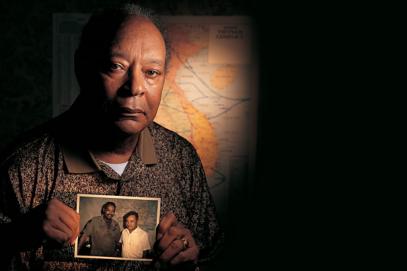

Luc has become a public figure since the lawsuit was filed, giving local and national interviews, putting a face to a community that is trying to be muscled out of youth sports. “I’ve lost count of all the messages and emails that say, ‘Thank you for what Luc is doing,’ ” Shelley says. “Luc has made such a big sacrifice, putting himself out there to help others knowing he might not get anything in return.”

Asked what he has learned about himself during this process Luc responds with a laugh, “It taught me I don’t like doing interviews.” Then the laughter quickly recedes. “But I don’t mind being uncomfortable because I’m fighting for what’s right.” Luc admits that he feels the weight of the lawsuit. “I feel pressure now on my golf, if that makes sense, like I put pressure on myself to play well. Now people want to know how I play all the time, and I don’t want to disappoint anybody.” Shelley later clarifies: “So many people who oppose this, their first question is usually, ‘Oh, he’s not even that great at golf.’ Well, that’s not the point. That’s not the point at all. It’s not because he thought he was some huge champion. He just wants to play golf.”

‘I DON’T MIND BEING UNCOMFORTABLE BECAUSE I’M FIGHTING FOR WHAT’S RIGHT.’

Although the family has received waves of support, this is a sensitive subject in a very divided country. Shortly after the lawsuit was filed, anti-LGBTQ protestors stood outside the corner from Luc’s school holding signs that read, “LGBTQ is a sin.” “I think they were upset about something else, not necessarily Luc, but it was a weird coincidence,” Mario says. “Even if Luc wasn’t the reason, imagine your kid seeing a group of angry people with signs trying to discredit your community.”

The lawsuit has hurt some relationships. One of Luc’s early golf coaches would not lend his support, and because they are employed by the state, many of the school’s teachers have gone silent. “I’m crushed,” Shelley says, “but I do realize there are political forces and other things at play.”

Even Mario admits to somewhat waffling at the idea of the lawsuit at first. The bill still allowed Luc the chance, if he wanted, to play on the girls team, a proposition Mario entertained. “I wanted Luc to be able to play, to have the camaraderie that makes sports so special. I saw he was hurting and thought, Well, not ideal, but it’s better than nothing,” Mario says. “But Luc put me in his shoes. He reminded me how weird it would look for a boy to be playing with the girls, that doing this would be doing exactly what the folks who put this cruel law into place wanted. Sometimes kids know better than adults.”

Luc is not oblivious to the noise, but his focus is elsewhere. Luc’s problem is time. Expediency is not the forte of the United States justice system. The lawsuit was filed in the fall of 2021, but the trial date is not until the spring of 2023. A lot can happen in that expanse, yet there’s a likelihood that Luc won’t get the opportunity to try out until his senior year. He has missed out on the bonding and shared experiences, the feeling of being part of a team. Those are precious years and years you get once. “It stinks,” Luc says, looking for other words but unable to find them.

So now Luc waits. He tries to focus on what he can control. At this moment, on a February day that has itself confused for March at Fairways and Greens Golf Center in Knoxville, that’s the short game. He’s a solid iron player, illustrated by his exhibition on the range, and plenty of pros would gladly take his putting stroke. What Luc lacks in distance he makes up for in accuracy. The chipping, though, needs work. He drops down a fist full of balls on a practice par-3 hole. He hits some chunks and skulls. Balls aren’t rolling out or rolling too far, and Luc is running hot.

“This makes me frustrated,” he says. “I spend too much time on my wedges for me to be hitting them this bad.” When I suggest we move on to the next hole, Luc refuses. “I have to get this right.”

Luc toils as I ask him more questions about the case, about the support and opposition and the idea of a 14-year-old facing down the Tennessee state government. He mostly demurs, transfixed on the task at hand, and the answer to the line of questioning is clear. Luc Esquivel just wants to play golf.